Should You Front Load Your Roth IRA?

First of all, there are actually two definitions to “front load” and I want to cover both in this blog post with you. The first definition is to contribute the max amount for the year to your IRA all within the beginning of the year. Meaning, you would contribute the full $6,000 ($7,000 if you’re age 50+) for the year in early January.

The second definition to “front load” is maxing out your retirement accounts when you’re younger and then getting to relax a bit as you get older, buy a house, have children, and other added expenses as life goes on.

I’m going to start with maxing out your IRA by contributing $6,000 as early as January 2nd of the New Year. This is something I have done, but is it all the beneficial? Would it be better to simply dollar cost average (invest on a monthly basis) into the market throughout the year instead? Maybe. I’ll share some data with you to give you my take on it.

There is a slight advantage to maxing out your IRA at the beginning of the year, but there’s a but to that and I will get to in a bit. The reason being, the full $6,000 is essentially in the market for a longer period of time than if you were to invest $500 per month ($500 x 12 months = $6,000/yr). By June, you would essentially only have $3,000 in the market, therefore your money is not in the market as long in comparison to dumping $6,000 in all at once.

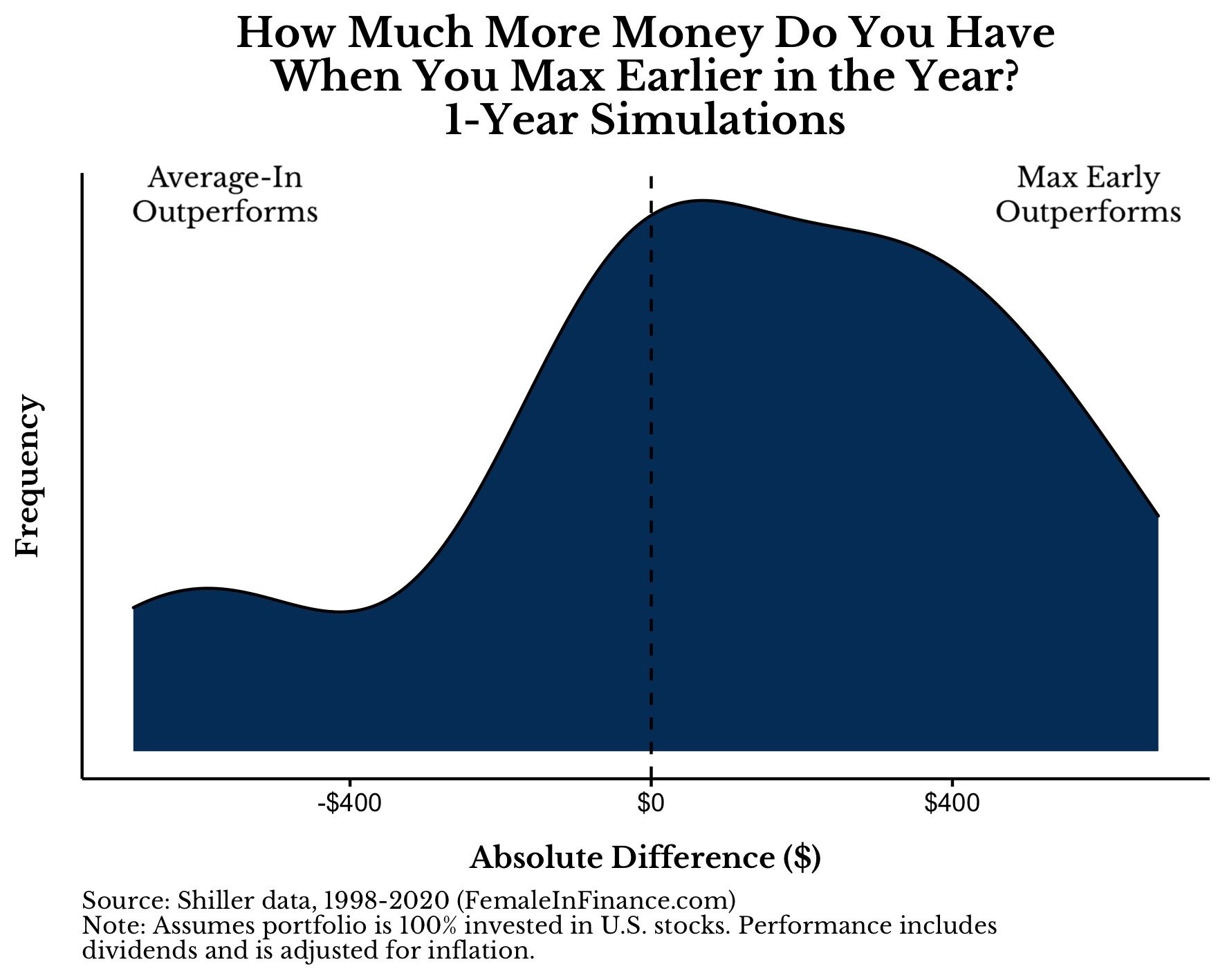

Below I will show you three separate simulations over a 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year period since 1998. The reason I chose 1998 was because that was when Roth IRAs were created. These simulations also assume a 100% S&P 500 portfolio with dividends reinvested (and adjusted for inflation).

First, let’s take a look at 1- year simulations.

If you were to front load your IRA by contributing $6,000 at the very beginning of the year versus dollar cost average into the market, you would see that the distribution is nearly symmetrical. The $0 dashed line is basically in the middle. This is because in some years, front loading your IRA would outperform dollar cost averaging, and in some years dollar cost averaging would outperform front loading.

The $0 dashed line in the middle can be looked at as which strategy for investing performs better. If the $0 dashed line were to the left, this would imply dollar cost averaging in would be better, and if the $0 dashed line were to the right, this would imply that there is much more outperformance when front loading your IRA.

This tells you that if you only plan to front load your IRA on a random year, it really won’t move the needle (insert shrug).

Statistically, lump sum investing at the beginning of the year would outperform dollar cost averaging into the market, but when you only plan to do it for a random year, it’s not going to be a difference you’ll notice when it comes to retirement.

Therefore, if there’s a year where you wanted to front load your IRA or thought you could, but didn’t, don’t beat yourself up. Just go make a sammich or something.

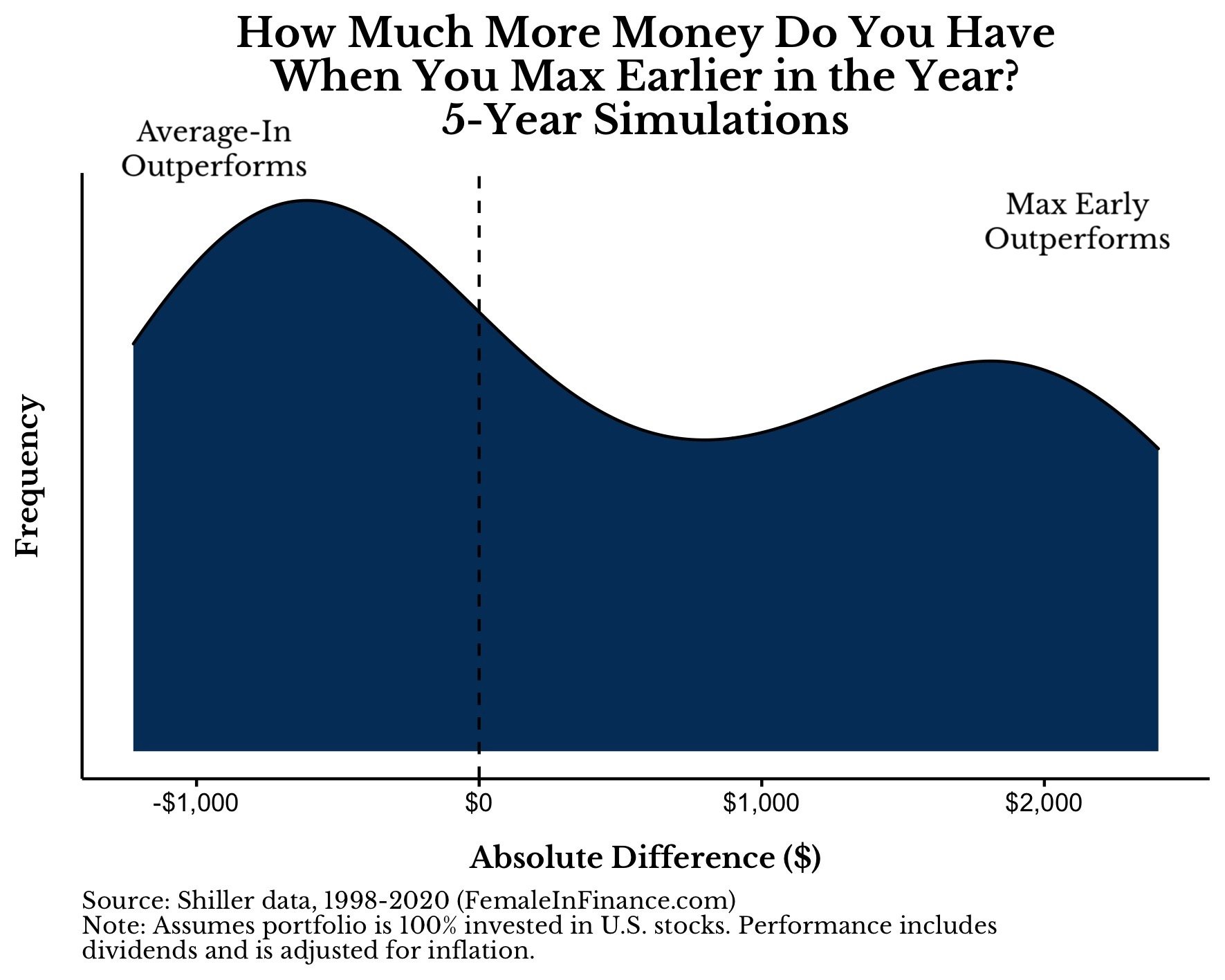

Now let’s take a look if you were to do this over a 5-year simulation instead of just one year.

Now the $0 dashed line is closer to the left a bit. This implies that over a 5-year period of front loading your IRA, that you would likely outperform dollar cost averaging into the market.

Still, with only $6,000 being the maximum contribution limit, it’s not going to be a HUGE difference when it comes to retirement, but there is a small advantage.

OkAy LeAnDrA, sO wHeN dOeS iT mAkE sEnSe tO fRoNt LoAd mY IRA?

It makes sense to front load your IRA if you do it for more like 10+ years in a row. Let me show you.

Now we’re talkin’.

The $0 dashed line is further to the left showing that over a 10-year period, front loading your IRA could make more of a difference. One year of front loading won’t make much of a difference (if any), however the data suggests that if you plan to front load your IRA over many years, that you will see an outperformance.

When it comes to your IRA, because the max contribution is only $6,000 per year, you’re not going to see a difference of millions of dollars in retirement just for front loading versus dollar cost averaging in.

401(k) has entered the chat.

But what about your 401(k). With a 401(k) you can contribute up to $20,500 per year in 2022. If you were to front load your 401(k), you would have the same results as far as it only being worthwhile if you do it multiple years in a row. However, this is obviously much less feasible as I don’t know many people dropping $20,500 in January into their 401(k)s. This is because you would basically need to be earning upwards of $246,000 per year to do this if you were to contribute 100% of your income in January to your 401(k).

If you’re earning that much over a 10-year period and you want to front load your 401(k) in January, then go for it and do a hair flip and call yourself “daddy” while you’re at. You’ll likely have more money in your retirement account compared to dollar cost averaging in by doing this.

If you plan to max out your 401(k) in the beginning of the year, please check with your employer that you would still receive your company match for the rest of the year. Not receiving your company match would make this strategy not worthwhile, and some employers will quit matching if you do this.

401(k) has left the chat.

Back to your IRA. You could expect to earn about 5% of $6,000 in a typical year by front loading your IRA. That’s about $300 per year. That’s why I say that doing this for one year, isn’t going to do much. But, doing this for 10+ years can make a difference.

At the end of the day, I don’t think you should cry in a corner if a year goes by where you could have invested $6,000 into your IRA in January, but didn’t. As you can see in the simulations, front loading for a longer period of time gives you greater odds of outperforming dollar cost averaging, but it’s not going to be the difference of you retiring 10 years earlier.

What about the second definition of front loading?

Don’t worry, I didn’t forget.

As I mentioned earlier, the second definition to of front loading is maxing out your retirement accounts when you’re younger and then getting to contribute much less as you get older and have more expenses in life.

By maxing out your retirement accounts, I’m talking about your 401(k) for $20,500 per year, your IRA for $6,000 per year, and a HSA (Health Savings Account) for $3,650 per year. That comes to a grand total of $30,150 per year which is equivalent to investing $2,512 per month.

Let me give you an example of what this could look like.

What I’m going to disregard is an employer match in my calculation. I’m disregarding increases in income over the years. I’m going to assume a reasonable 7% rate of return. And I’m going to base my example on maxing out your retirement accounts for 10 years starting at age 25, and compare it to someone who maxes out their retirement accounts for a 30-year period from ages 35-65.

Now, let’s give you some characters.

Stacy is a 25-year old professional stand-in bridesmaid. Meaning, strangers hire her to be their best friend on their wedding day. She is maxing out her retirement accounts for the next 10 years and then quitting all investments to her retirement accounts thereafter. Can you guess how much she would have by the time she hits retirement age of 65? Take a guess, but I’ll let you know, shortly.

Next character is Jack. Jack either didn’t learn about investing for retirement until later in life or he was YOLO-ing his money. Either way, he started investing later in life. Jack works as a veterinary acupuncturist (is that even a thing?) and he maxes out his retirement accounts from age 35-65. Therefore, he’s starting a little later and not front loading (maxing out his accounts early into his career).

Who ends up with more money in retirement? Stacy or Jack?

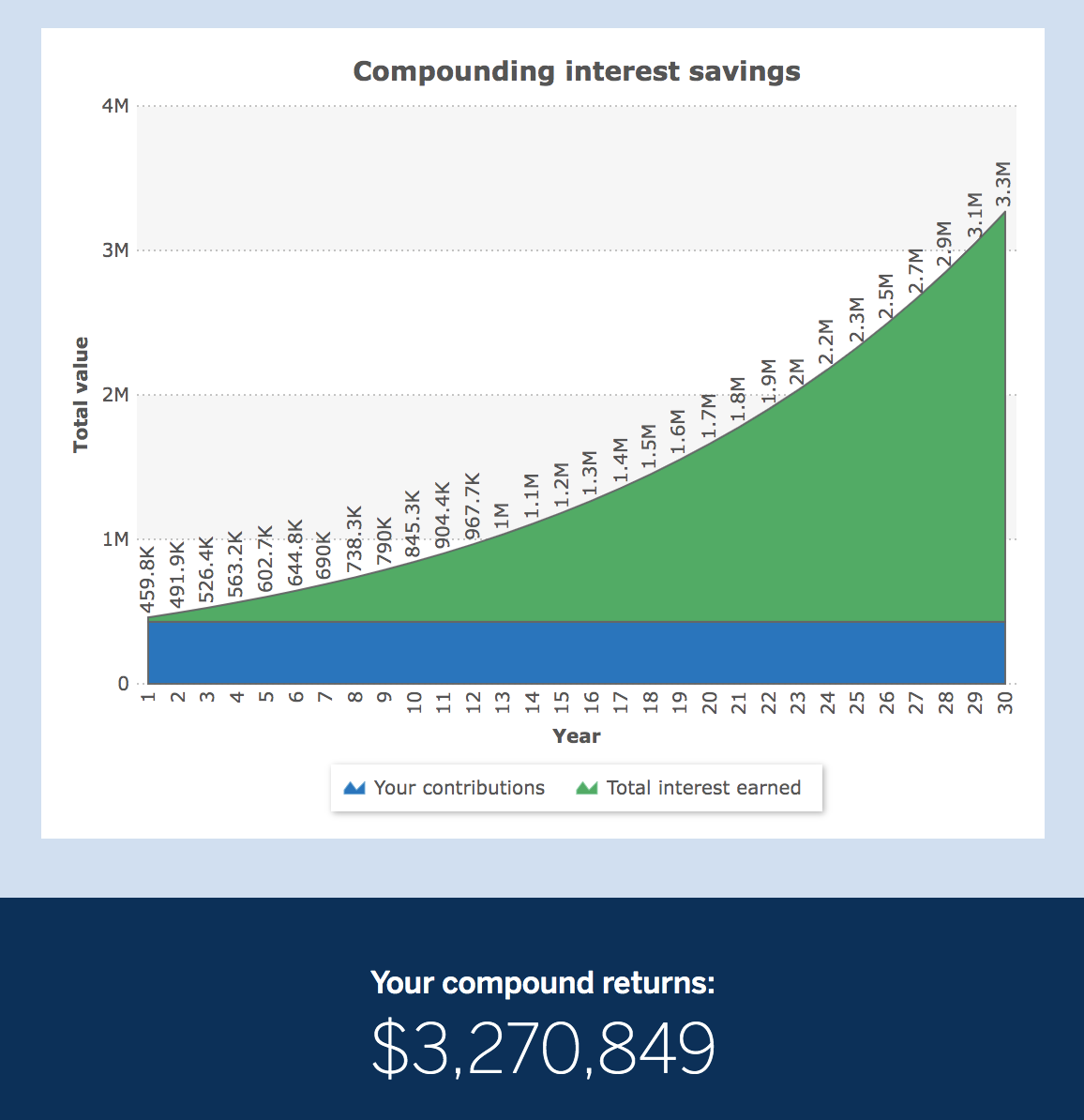

Let’s start with Stacy. If Stacy invests $2,512 per month ($30,150/year) for 10 years from age 25-35, she would have invested $301,440 of her own money. Remember, this means she’s maxing out her 401(k), IRA, and HSA every year for 10 years in a row.

Assuming a 7% rate of return, in 10 years Stacy would have $429,682 in her retirement account.

Stacy leaves the $429,682 in her retirement accounts and rage quits. Meaning, she no longer contributes to any of these retirement accounts until retirement (age 65).

30 years later, Stacy would be 65 and would have $3,270,849 for retirement.

Holy shit, right?

Can you imagine grinding for 10 years, never investing again, and retiring with $3.2M?

Essentially 9.2% of the total value of the investment is what Stacy put in, and compound interest took care of the rest.

By Stacy front loading (maxing out retirement accounts early in her career), she is given much more freedom with her income from ages 35-65.

Now, what about Jack?

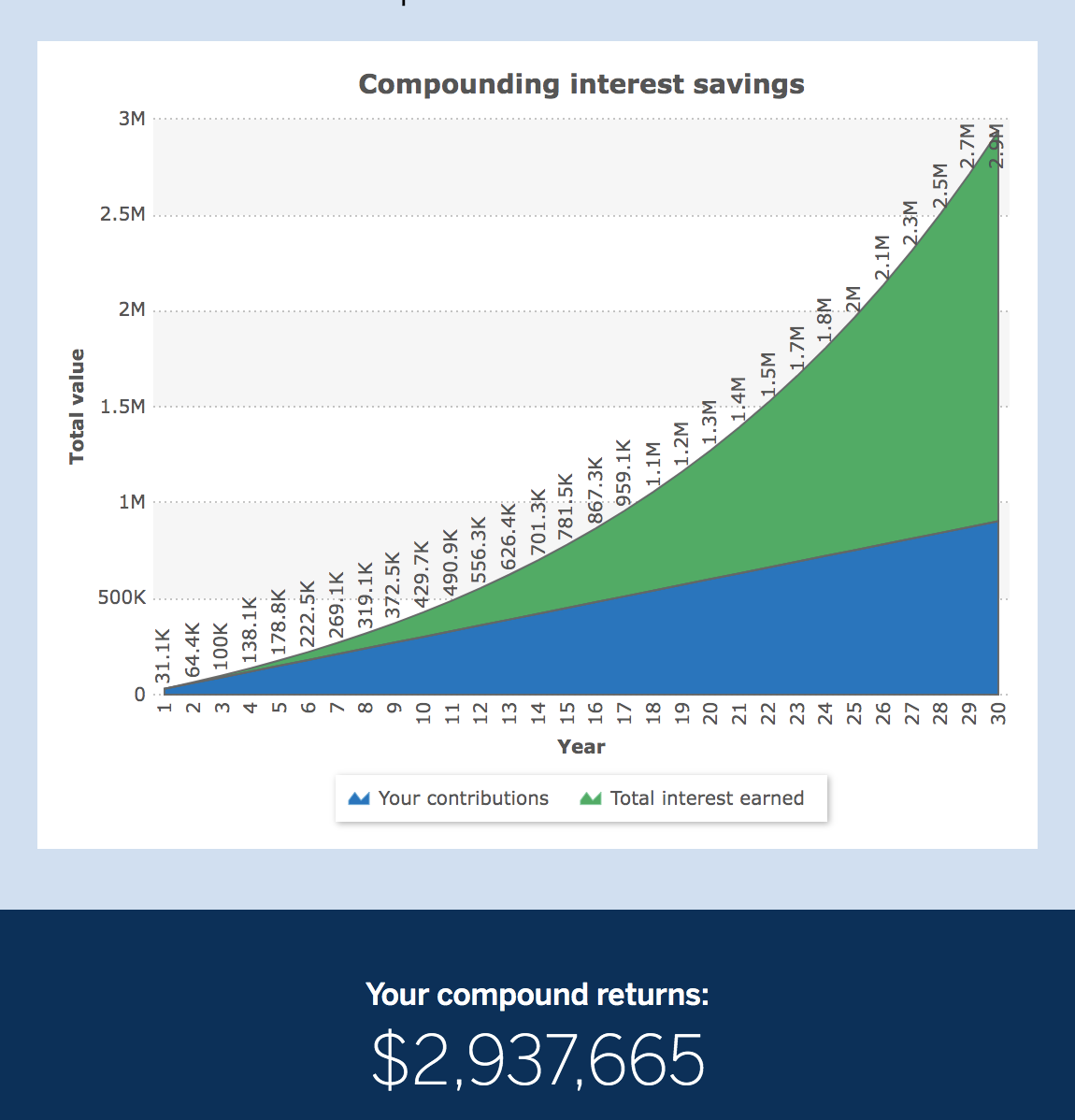

Jack invests $2,512 per month ($30,150/year) for a whopping 30 years. He’s maxing out his retirement accounts from ages 35-65.

Typically during this age, you may have more expenses than you would from ages 25-35. You may have more expensive things like a mortgage, children, five dogs, etc.

Jack ends up investing a total of $904,320 of his own money.

By the time Jack is 65, his money has grown to $2,937,665. This is also assuming a 7% rate of return.

Jack invested just over 3x more money than Stacy, and still ended up with $333k less than Stacy.

30.8% of the total value of the investment is what Jack put in, and compound interest took care of the rest. That’s a lot more than Stacy, who’s total contributions were only 9.2%.

How is this possible?

Compound interest’s greatest variable is TIME. If your money is in the market for a longer time, you could invest much less money and still end up with more money in retirement than someone who invests later in life.

Now, if you’re already older than the age of 25, don’t beat yourself up. You can go play a single, sad Adele song, and then get over it. The point is, the power of starting early is HUGE (insert Donald Trump’s voice). And if you haven’t started yet……..please start now.

For funsies, I ran a calculation on if Stacy continued maxing out her retirement accounts through age 65, and she would have $6,208,514 by age 65, again assuming a reasonable 7% rate of return. Impressive.

Money is a tool.

When we look at the numbers in this single example, it’s easy to say, “okay Leandra, I’ll front load my retirement accounts for 10 years.” You can create a lot of flexibility in your life by investing for a 10-year period very early. But what’s the downside? I’ll let you determine that, because there’s a lot of assumptions that could be made about Stacy.

You could think Stacy didn’t truly live if she was investing that much money from 25-35. Or you could think that she was maybe given some money from her parents. Or you could assume that Stacy had zero fun and is now suffering in other areas of life because she was so aggressively investing at a younger age. Or you could just assume she earned her way to a high paying job at a younger age and was investing 20% of her income. I’d hope Stacy had high income and was financially literate, but that won’t be the case for everyone.

The bottom line: Front loading your retirement accounts earlier in life gives your money more time to compound. As long as you can invest and there’s no major sacrifice or detriment to other ambitions in your life, then invest as early as you can.

Time in the market > How much money invested in the market.

Cheers.

LP